In our first Fellows blog post of 2026, Atomic Anxiety Fellow Franco Castro Escobar reflects on how fear plays an integral, multiple role in nuclear policy...

People are not born anxious about the nuclear threat. Neither are we innately angry, apathetic, optimistic, or reassured by nuclear weapons. Most of us, instead, arrive in this world unaware of nuclear things.

We remain like that for short or long periods of time depending on the stories and events that shape our understanding and experience of the nuclear world. I say ‘most of us’ because some people have experienced nuclear explosions from as early on as their day of birth (or while still in-utero), and others may go about their lives without much, if any, atomic anxiety at all.

My research explores why some young people join antinuclear groups, and how they became acquainted and concerned with the concept of ‘nuclear weapons’. I am interested in this process (or lack thereof) — usually known as ‘political socialization’ or ‘nuclear learning’ — because it guides the information, values, identities, and actions undertaken (or not) in response to perceived nuclear prospects and issues such as abolition, accidents, colonialism, deterrence, disarmament, miscalculation, peace, stability, war, and so on.

For Jeffrey W. Knopf (2012), the process of nuclear learning goes beyond the flow of basic facts, and includes the larger implications that can be inferred from those facts, the rethinking of ends being sought, and the adjusting of chosen means.

In 1963, Günther Anders described ‘anxiety’ in relation to the nuclear age, not as an observable quality of people, but as a tool to make the fearless and the fearful incapable of feeling fear. Anders writes:

it is our capacity to fear which is too small and which does not correspond to the magnitude of today’s danger. As a matter of fact, nothing is more deceitful than to say, “We live in the Age of Anxiety anyway.” This slogan is not a statement but a tool manufactured by the fellow travellers of those who wish to prevent us from becoming really afraid, of those who are afraid that we once may produce the fear commensurate to the magnitude of the real danger. On the contrary, we are living in the Age of Inability to Fear” (1963, p. 498).

Anders believed people should be free to fear nuclear weapons (as opposed to free from fear). He thought people should have “the courage to be frightened, and to frighten others, too” (p. 498), because fear can bring people to the streets, not just under cover.

The larger implications of the nuclear threat require that ordinary democratic citizens become concerned with nuclear issues even if these seem beyond their professional competence — or far from their geographical and temporal proximity.

Given that renowned physicists have been dismissed as incompetent and discouraged from ‘meddling’ with nuclear politics, Anders rejected the idea that political elites are necessarily better able to picture nuclear dangers than ordinary people. He writes:

This pre supposition is even irresponsible. And it would be far more justified to suspect them of having not even the slightest inkling of what is at stake (p. 499-500).

‘Atomic anxiety’ — understood as a collective “fear of death en masse resulting from the notion of nuclear weapons use” — is therefore said to be a spontaneous, pervasive, and authentic emotional response to the nuclear threat (Sauer 2015: 174).

But the concept primarily refers to a feeling experienced (or ‘endured’) by a group of high-level nuclear decision-makers who (while themselves afraid of nuclear annihilation) ensure that nuclear weapons are not used by playing a double role:

- Create fear by putting forward deterrence-based policies that seem risk-prone, irrational, and aggressive; while simultaneously;

- Reassure the public about their safety, preventing them from ‘panicking’ in ways no nuclear-armed state desires.

Understood as such, ‘atomic anxiety’ resembles not just a collective feeling, but a process of knowledge, emotional, and behavioural management.

Following this argument: a group of decision-makers (privileged with seemingly unique access to information otherwise unavailable to the public) intend to oversee what certain groups of people know, feel, and do. They administer the flow of basic facts and signal the broader implications of said facts to the public, allies, and adversaries.

The goals are twofold: (a) avoiding the use of nuclear weapons and (b) stifling public dissent with deterrence-based policies. Both goals are achieved by the same means: fear management.

While fear and anxiety take a central role in the discussion as I have framed it above, this is an incomplete picture of the emotional responses elicited during nuclear learning (i.e. during the acquisition of basic facts about nuclear weapons, and broader implications, ends and goals). Somewhere in between the fearful and the fearless (or those incapable of feeling fear), are all of us.

In my research, I ask politically active youth, ‘when did you first encounter the concept of nuclear weapons?’ and ‘can you say more about that?’

Responses to these questions are not limited to anxiety. Ask yourself: Do you recall the first time you encountered the concept of nuclear weapons? What did you feel? Did you feel reassured? Shocked? Afraid? Bored? Confused? Disgusted? Exhausted? Outraged? Powerless? Proud? Sad? Ashamed? Or perhaps something else… More importantly, what did you do next? And what about the last time you heard about ‘nuclear weapons’?

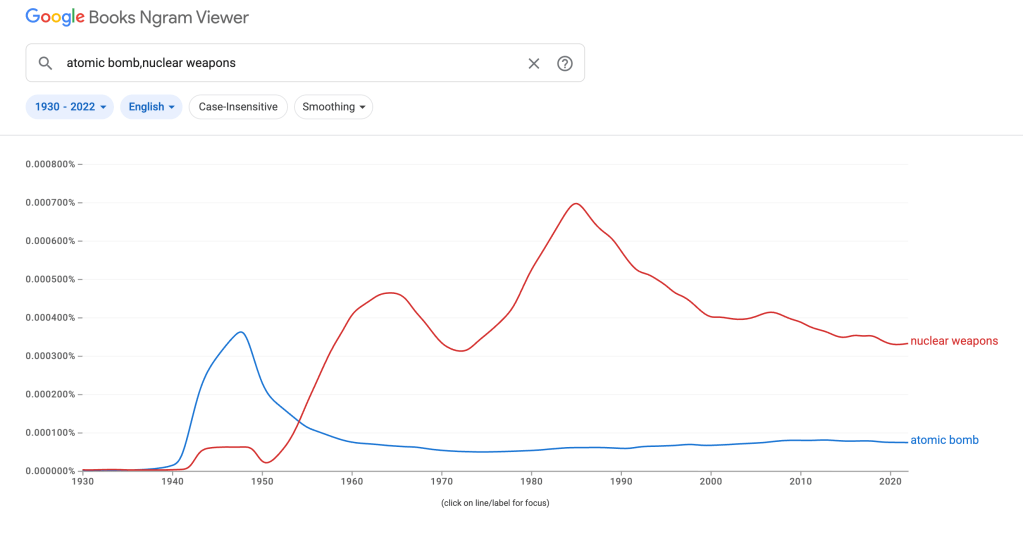

Using the tool Google N-gram, the graph above shows the waxing and waning in salience of the concepts of ‘nuclear weapons’ and ‘atomic bomb’ within Google’s corpus of books published in English.

The three crests of activity coincide with the three waves of global antinuclear activism during the Cold War (Note: some of these groups have been regarded as anxious, hysteric, radical, or irrational).

Since the highest peak around 1984, the concept of ‘nuclear weapons’ has declined to a relative prominence which, in 2020, is comparable to that of 1958, 1970, or 1974 — also comparable to the relative prominence that ‘atomic bomb’ had in 1946-1948.

How did we feel then? How do we feel now? What should we do next?

Franco Castro Escobar is a PhD candidate at Keele University’s David Bruce Center for the Study of the Americas and a research fellow at the Hiroshima Peace Institute.

His research focuses on youth involvement in nuclear disarmament, aiming to better understand how and why young people join or create anti-nuclear youth-based organizations. Franco is creating the first anti-nuclear youth oral history archive, documenting the stories of young activists to help them reclaim authorship in the Nuclear Age.

This blog is part of a series of articles by the Atomic Anxiety in the New Nuclear Age Fellows Cohort. These articles represent the view of the author and not necessarily those of the project as a whole or other individuals associated with the project.

Leave a comment