Thirty years since the signing of the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon Free Zone, Hree P. Samudra reflects on what causes her atomic anxiety in the latest of our 2025 Atomic Anxiety Fellows cohort blogs…

Atomic anxiety, for me, means watching an institution preserve itself while abandoning its core function. It means seeing ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) reaffirm their commitment to nuclear-free principles while producing no unified response to violations. Both of these realities coexist indefinitely.

The Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone celebrated its thirtieth anniversary this year. That’s three decades of institutional presence while the strategic environment deteriorated systematically around it.

When China announced in July 2025 its readiness to sign the SEANWFZ protocol without reservation, regional capitals celebrated. The reasoning was straightforward: it was a nuclear armed state constraining itself.

However, China gained formal credibility while actually preserving complete operational flexibility to deploy nuclear armed submarines in treaty-protected waters.

I want to be precise about what happened here. China understood the verification architecture better than ASEAN member states acknowledged publicly. SEANWFZ verification relies on state-to-state reporting and IAEA safeguards with no independent inspection authority, which means submarines cannot be effectively monitored.

Tariq Rauf, former Head of Verification at the IAEA, documented the practical reality that nuclear navies using weapon-grade highly-enriched uranium are fundamentally uninterested in allowing inspectors near their nuclear fleets. This is an operational requirement, not bureaucratic preference. Nuclear powers need submarine transit flexibility for deterrent patrols and the right to deploy weapons outside the zone if core interests face an existential threat.

China signed the SEANWFZ protocols precisely because the treaty grants exactly what Beijing demanded: operational freedom beneath ceremonial compliance. The treaty works for China because it was built to work for nuclear powers.

Consider what this means materially. Satellite imagery reveals six nuclear submarines at Chinese bases as of October 2025. Yet ASEAN’s collective response has been silence at the institutional level. Why? Because ASEAN cannot respond as member states face genuinely incompatible security calculations.

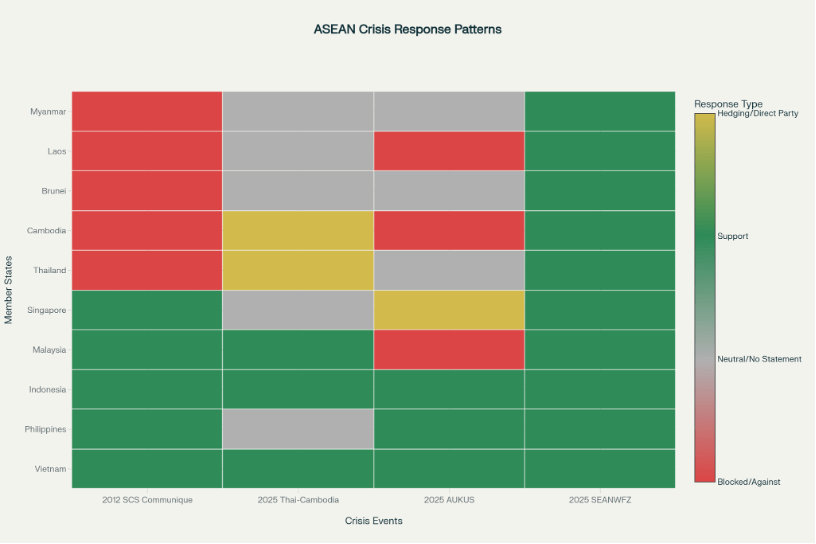

The Philippines needs public condemnation to justify US alliance deepening. Thailand requires strategic ambiguity to preserve hedging between Beijing and Washington. Cambodia aligns explicitly with Chinese security interests. Vietnam voices concern but refuses commitment to collective action that might escalate tensions. These aren’t policy failures, but survival requirements.

This pattern emerged clearly in 2012 when Cambodia blocked a South China Sea Joint Communique criticizing China because Beijing offered economic incentives for Cambodia’s veto. More recently, in July 2025, Thai and Cambodian forces fought across their border for at least 38 days with approximately 38 deaths and over 275,000 civilians displaced, yet ASEAN produced no unified statement.

If ASEAN cannot respond to kinetic warfare between members, can it really constrain external actors possessing nuclear weapons in the Southeast Asia Nuclear Weapon Free Zone? The organisation does not lack institutional tools. It lacks structural capacity to enforce them against member states with incompatible interests.

Even so, SEANWFZ has had some success. No member state conducted nuclear weapons tests since the treaty’s ratification in 1996, though this reflects the absence of preexisting nuclear programs among ASEAN states rather than the treaty’s constraining power alone.

ASEAN member states have also collectively endorsed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, with Vietnam among the original signatories. Notification protocols for military exercises near treaty boundaries have reduced accidental miscalculation risk, and the zone created communication channels and normative expectations where none existed before.

SEANWFZ’s thirty-year persistence demonstrates genuine regional identity. Member states truly believe nuclear weapons are abnormal in Southeast Asia. That belief is authentic, and these are genuine accomplishments.

However, while SEANWFZ might constrain behavior, it does so only in peacetime. The moment a crisis arrives, the framework’s actual constraints become visible. If, or when, a militarized crisis arrives with Taiwan, implications cascade through nuclear hedging calculations extending far beyond Southeast Asia.

Under Vipin Narang’s nuclear proliferation framework, Japan and South Korea represent insurance hedgers, meaning they maintain nuclear technical capability as insurance against US extended deterrence abandonment. If Taiwan falls and US credibility collapses in the region, both states would face intensified pressure to reconsider their non-nuclear status. SEANWFZ’s inability to constrain regional nuclear presence would compound these calculations

The broader region seems like somewhat of a crisis environment. China possesses approximately 600 warheads and adds roughly 100 annually, India operates nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, Australia will soon station nuclear-powered submarines with over 1,200 US and UK personnel in Perth, and no regional institution can truly constrain nuclear presence.

ASEAN member states have fragmented in the face of these issues. In regard to AUKUS, for example, Indonesia and Malaysia criticized it immediately. Vietnam supported it quietly. The Philippines backed it explicitly. ASEAN produced no collective response.

The SEANWFZ operates as a peacetime framework, and it will likely persist as a symbolic framework because the cost of disbanding it exceeds the cost of maintaining it while acknowledging its operational limits.

This is not criticism. This is a diagnosis. In peacetime, all members can affirm that nuclear weapons are abnormal in Southeast Asia. Consensus exists because consensus costs nothing. In a crisis, consensus becomes permission for inaction.

When China’s submarines operate without ASEAN response, this is not treaty failure. This is the institution performing its actual function. The design permits exactly what is happening.

Atomic anxiety, for me then, is about understanding that distinction clearly. It is recognizing that the framework for the SEANWFZ will indefinitely reaffirm commitment to nuclear-free principles. But so too will the framework also indefinitely produce no unified response to violations.

When strategic restraint mechanisms collapse at the global level, like they currently are through the collapse of arms control treaties and rising tensions, regional frameworks become even more brittle. Nuclear-armed states gain freedom at the moment regional institutions lose capacity to respond. This is not inevitable. But it is the trajectory we are observing.

Hree P. Samudra is a nuclear policy advocate, analyst, and researcher based in Jakarta, Indonesia. She is Asia-Pacific Regional Coordinator for Youth for TPNW and currently serves as a CTBTO Research Fellow. Her work examines institutional capacity and effectiveness in regional arms control frameworks, with particular interest in how consensus-based mechanisms operate during security crises in the Indo-Pacific.

This blog is part of a series of articles by the Atomic Anxiety in the New Nuclear Age Fellows Cohort. These articles represent the view of the author and not necessarily those of the project as a whole or other individuals associated with the project.

Leave a comment