In the latest of our 2025 Atomic Anxiety Fellows cohort blogs, Rebekah K Pullen writes about popular culture, atomic anxiety and how ‘the devices outgrew us’…

Reflecting on the concept of anxiety in the nuclear space, I wonder if I’m driven to research nuclear weapons to assuage my own fears. My PhD research considers political theories of violence as they relate to cultural narratives regarding nuclear weapon use.

Essentially I’m curious about how nuclear weapons are expressed as both a cultural artefact and a security ‘tool’, especially in terms of popular culture and entertainment, such as in the recent blockbuster hits Oppenheimer (2023) and House of Dynamite (2025). In short – amongst other things – I watch movies with nuclear weapons in and analyze their politics.

Occasionally, I’m asked if it’s ‘overwhelmingly depressing to think about the end of the world all the time’ (the phrasing varies, but the question has been posed in those exact words). And while I try to cultivate outside interests, the nature of my research means that I’m somewhat embedded in my work-space even when ‘offline’; and it does involve imagining nuclear war.

So, I do feel ‘atomic anxiety’ – a sense of powerlessness in the face of a seemingly inevitable nuclear doomsday (related to what Benoît Pelopidas calls “nuclear eternity”) – in response to watching some of the most famous, or infamous, nuclear weapon films.

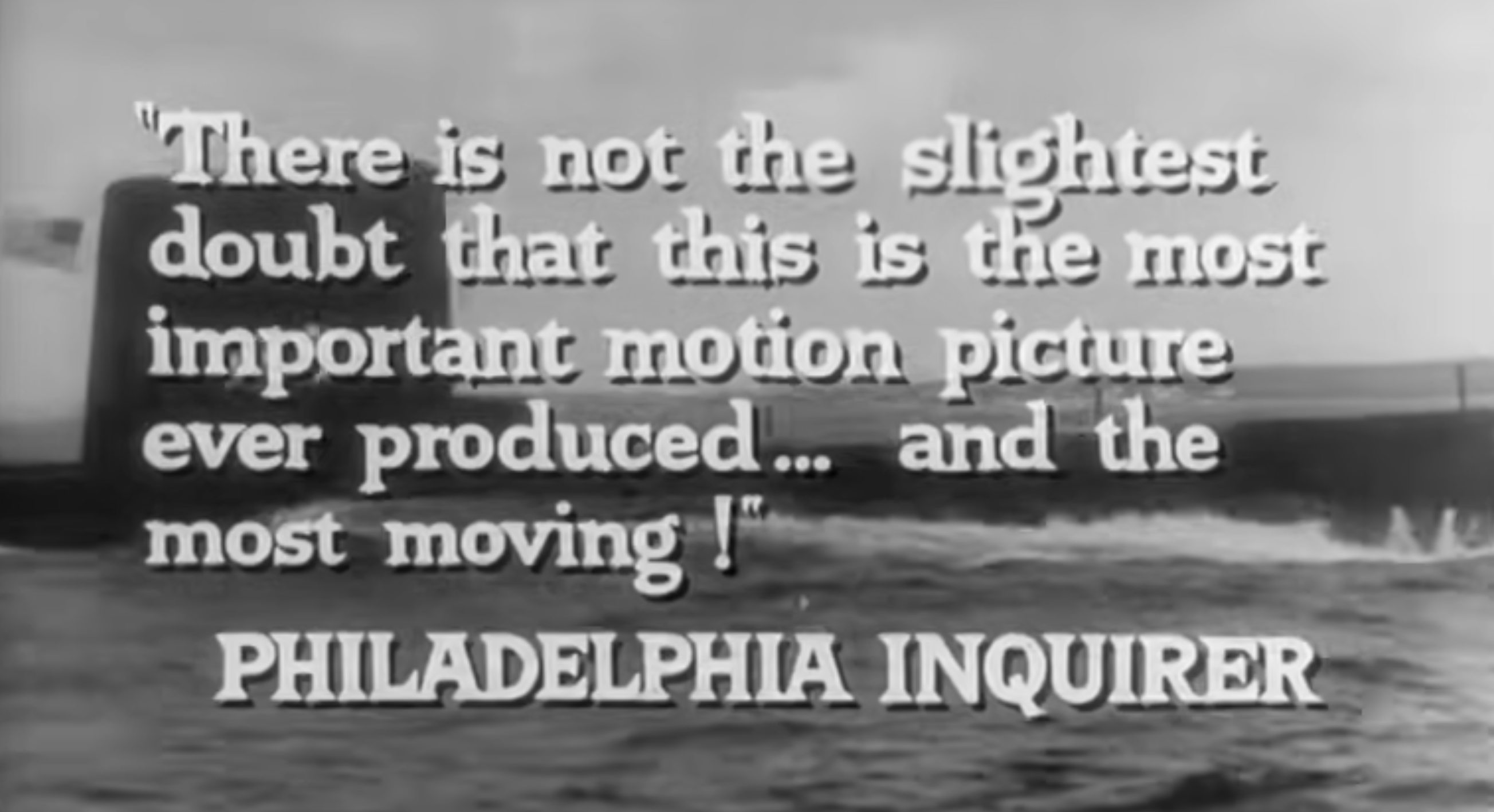

One of my favourite films to recommend, particularly to those exploring their own feelings of atomic anxiety, is Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), which features many notable actors including Anthony Perkins (who would go on to play Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho), Ava Gardner, and Fred Astaire.

On the Beach takes place in the aftermath of a global nuclear war. The rest of the world has been destroyed and the only survivors live on the coast of Australia. Suspending our disbelief (as is often called for in movies) regarding the science of radioactive fallout, people try to live normal lives as they wait for the fatal radiation cloud to make its inevitable way down to them from the northern hemisphere.

Unable to completely ignore their impending doom, social gatherings often lead to discussions about why the war happened. In a departure from his most famous roles, Fred Astaire plays Julian, a former atomic scientist that the film establishes as having expert knowledge. When first asked ‘How did it start?’, he seems reluctant to give a serious answer and glibly responds, ‘Albert Einstein.’ But when pressed, he describes a scenario that feels as inescapable as it is unaccountable:

‘Do you really want to know who I think started the war? […] Who would ever have believed that human beings would be stupid enough to blow themselves off the face of the earth? […]

The trouble with you is you want a simple answer, and there isn’t any. The war started when people accepted the idiotic principle that peace could be maintained by arranging to defend themselves with weapons they couldn’t possibly use without committing suicide.

Everybody had an atomic bomb and counter bombs and counter-counter bombs. The devices outgrew us; we couldn’t control them. I know, I helped build them, God help me.

Somewhere, some poor bloke probably looked at a radar screen and thought he saw something; knew that if he hesitated one thousandth of a second his own country would be wiped off the map, so – so he pushed a button. An-and, the world went crazy. And…and…’

Not only is this scene distressing, his explanation touches on multiple ‘real-world’ elements that feed into my atomic anxiety: the expanding role of technology in identifying and analyzing threats; the potential ramifications of the rigid policy structures shaped by nuclear deterrence theory; the risks of path dependency; how nuclear weapon states anticipate an ever-narrowing window of time to decide how – or if – to respond to a nuclear attack. There is a lot to feel anxious about, whether actual or imagined.

Nuclear weapons are fundamentally integrated into the current international order, influencing how every state frames their participation in the international community. And since the ‘birth’ of the nuclear age, they have loomed large in our global consciousness because of their exceptional destructive power.

The Manhattan Project scientists who wrote the Franck Report, advocated against using the first atomic bombs on Japanese cities because they recognized that “in nuclear weapons we have something entirely new in the order of magnitude of destructive power.”

Since 1945, advances in technology have allowed for more powerful weapons as well as more comprehensive analyses. For example, a team of multi-disciplinary researchers have built scientific models to hypothesize the global environmental impacts of nuclear war or, more colloquially, to describe ‘nuclear winter’.

Among various grim predictions, they conclude that a “regional nuclear war” (involving the detonation of one hundred 15 kt weapons) would generate a “global cooling” that “could persist for more than 25 years”. For context, there are approximately 12,241 nuclear weapons in the world; and the 15 kt bomb dropped on Hiroshima killed approximately 140,000 people.

Seventy-five years after the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the leaders of multiple international and national Red Cross/Red Crescent organizations published an open letter clarifying that, “any nuclear blast would cause insurmountable challenges for humanitarian assistance and that adequate assistance capacities do not exist at national or international levels” (emphasis added).

And yet, we’ve seen a resurgence of investments in nuclear arsenals around the world. This is what I can’t stop thinking about when Astaire’s character laments, ‘The devices outgrew us.’

I once had a colleague share he was drawn to his particular research focus because it was “the thing that made [him] the most angry”. Reflecting on my work, I certainly have moments of anger; I can feel frustrated, afraid, or annoyed by what I see in the news or what I learn from my research. But overall, nuclear weapons aren’t what make me the most angry; they’re what make me the most confounded.

Why aren’t more people angry about the increasing risk of nuclear violence? Why aren’t more people anxious about the limited global emergency preparedness? Why aren’t people more anxious or angry? I’m overwhelmingly curious: why isn’t everyone talking about nuclear weapons all of the time?!

This is the other side of my atomic anxiety. We live in a world bounded by nuclear violence and we seem to have gotten used to it. We (myself included) convinced ourselves to live with it, to live as normally as possible while waiting for the inevitable. We even made nukes entertaining. But living under perpetual existential risk is not normal, and we should question why we think it is.

It can be overwhelming to regularly engage with so many versions of global catastrophe, both historical and imagined. But that’s why I think it’s important to explore the everyday ways we talk about nuclear weapons when we see them as fictional. These stories can be both an outlet for avoidance and an avenue for engagement. The characters we position as the heroes and villains of nuclear narratives can clarify how we’re willing to engage with the idea of nuclear destruction.

Moreover, framing nuclear weapons as instruments for storytelling, rather than security, can make our atomic anxiety more accessible and encourage curiosity.

We can ask (more) questions about what makes us angry, or afraid, or annoyed about living in a world with nuclear weapons. I know this focus and curiosity helps me; perhaps it can help more of us understand atomic anxiety and its effects.

Rebekah K. Pullen is a PhD Candidate in International Relations at McMaster University, where her dissertation explores depictions of decision-maker agency around nuclear weapons in film.

This blog is part of a series of articles by the Atomic Anxiety in the New Nuclear Age Fellows Cohort. These articles represent the view of the author and not necessarily those of the project as a whole or other individuals associated with the project.

Leave a comment